Climate Change:

A Practical Guide to Legal

& Financial Levers for Cities

& Border Cities

Promoting the resilience of border cities to climate change

Africa played an active role in the COP21 negotiations, emphasising the importance of cities at the forefront of climate resilience and the need for mechanisms to finance adaptation to climate change. Many opportunities exist for fostering cross-border co-operation between local authorities. However, given the lack of suitable legislation and funding, local authorities do not always have the means to carry out cross-border projects and the ability to directly access climate finance.

The work of the Secretariat seeks to better understand the environmental constraints that affect cities in cross-border areas. The work reviews international funding sources. It assesses the legal, financial and governance options that could help local authorities carry out cross-border projects.

The Secretariat completed two case studies in Dori (Burkina Faso) – Tera (Niger), Gaya (Benin) – Malanville (Niger) and one ongoing study along the Lago (Nigeria) – Abidjan (Cote d’Ivoire) corridor. This work feeds into advocacy efforts following the Paris Agreement to provide cities and local authorities with access to climate finance, within the framework of the Climate Task Force of the United Cities and Local Governments of Africa (UCLG Africa).

De l’idée à la préparation d'un projet transfrontalier

De l’idée à la préparation d'un projet transfrontalier

Objectives of the Guide

Present a diagnosis of the technical and financial engineering available to local and regional authorities and even cross-border structures for adapting to climate change.

The analysis performed is not exhaustive and the list of financial mechanisms is evolving. However, the proposed methodology, in addition to the legal and financial mechanisms listed, can be adapted by stakeholders demonstrating the political will for climate project delivery.

Impact

- Local authorities and cities will be better able to assert their role in formulating climate risk mitigation policies.

- Improved knowledge of climate finance for cross-border bodies, as well as of legal levers and financial support for border co-operation.

The Guide

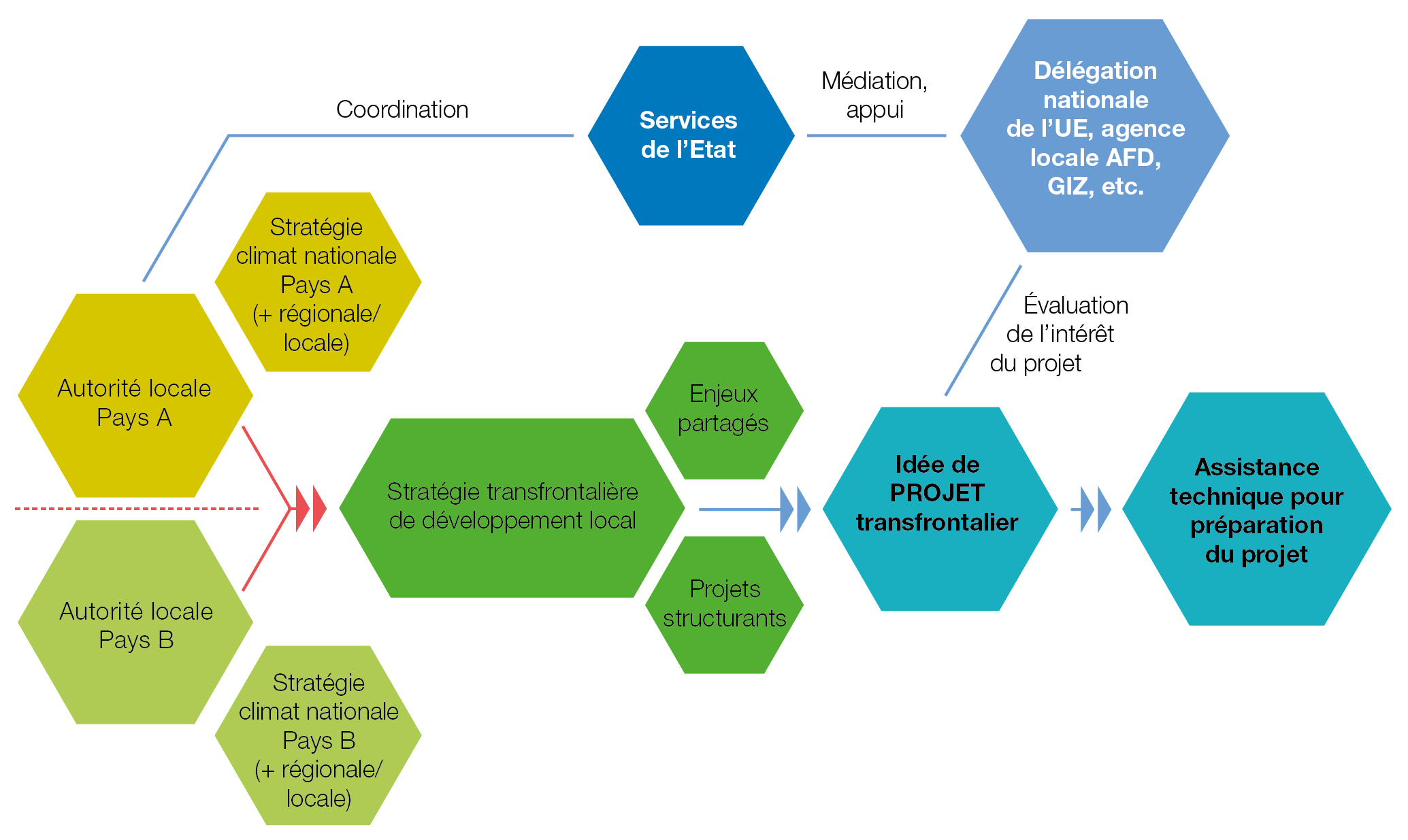

No. 1 : The project-planning process

A cross-border climate adaptation project is implemented in a series of steps. This process is the same for all of the various stakeholders, including those who are already at a stage in which co-operation is underway and can therefore skip the steps that have already taken place.

No. 2 : Establishing and local and national climate change strategy

The drafting of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies at the national level is recommended in the United Nations (UN) Conference of the Parties (COP) framework and supported by the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) process for Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The objective is to support country risk assessments related to or reinforced by climate change and to develop an action plan to reduce vulnerabilities.

No. 3 : Establish a cross-border local development strategy

Cross-border regions are living areas in which populations often share the same cultural and linguistic features, as well as specific needs for territorial development, which is particularly the case when a capital city is far from the border. Some of these specific needs are accessibility to basic services like health and education/training, facilitating trade in cross-border markets, territorial development and cross-border transport.

Mobilising local political and technical stakeholders to create partnerships around a cross-border territorial project is essential for concerted territorial development that does not negatively impact neighbouring countries (ex. flood control hydraulic structures on the Niger River) and that take into account population flows around infrastructure (markets and related services, health centres, etc.).

No. 4 : Setting up a cross-border project

The setting up of the project itself, within the framework of a call for projects, or in order to be submitted to the evaluation of national (state services), regional (ECOWAS, UEMOA, African Development Bank) and international funders, must undergo rigorous strategic thinking to consider and anticipate the needs and risks at each stage of the project.

The cross-border project’s legal framework depends on the purpose of the co-operation, its duration and the stakeholders involved. The aim is to determine the appropriate legal framework for carrying out the cross-border project. The following should be identified for each co-operation framework:

- Cross-border co-operation areas of interest: what is the purpose of cross-border co-operation?

- The value added of an ad hoc cross-border co-operation framework with regard to existing initiatives

- The most relevant level of organisation: what geographical coverage and what level of decision-making?

- The partners concerned: socio-economic, institutional stakeholders; broad or restricted co-operation framework

- Duration of the partnership: is this long-term co-operation or ad hoc?

- The most relevant legal tool to formalise the preferred co-operation framework

- The legal transcript of partners’ expectations.

To note

The legal structure issue (last two points) arises when all of the first five points have been determined. The concertation framework can take various forms: from a simple agreement to a dedicated joint permanent structure, the choice of the legal framework therefore depends on the goal of the co-operation, its duration and the stakeholders involved. It is clearly not recommended to have too many concertation frameworks. Nevertheless, there may be several cross-border co-operation frameworks for the same territory for different purposes. Co-ordination is essential between these different types of co-operation so as to promote synergy among the actions and avoid competition situations that would be counterproductive (duplication of efforts).

No. 5 : Structure the project around available technical engineering

Financial and technical engineering to build local capacities: tools for decentralised co-operation

Exchanges between local authorities of the North and South, with the participation of technical agencies, can provide knowledge and technical know-how within the framework of specific projects needed to carry out certain adaptation and development actions in West Africa. These exchanges may involve only local authorities or agencies with technical expertise. Funding schemes conceived to encourage decentralised co-operation can then be mobilised and help provide the required technical and financial assistance.

The transfer of financial and technical assistance to institutions at the regional level in Africa

Regional institutions in Africa also present technical and financial assistance for climate action projects, which could where appropriate be multi-country. This assistance may be provided by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or the African Union. The African Development Bank (AfDB) becomes the strong arm of the Green Climate Fund in African States and other regional funds for resilient infrastructure development; and programmes independent of the African Development Bank. The following are some programmes that can support climate change adaptation projects - potentially cross-border and fund initiatives for sustainable and resilient development in West Africa.

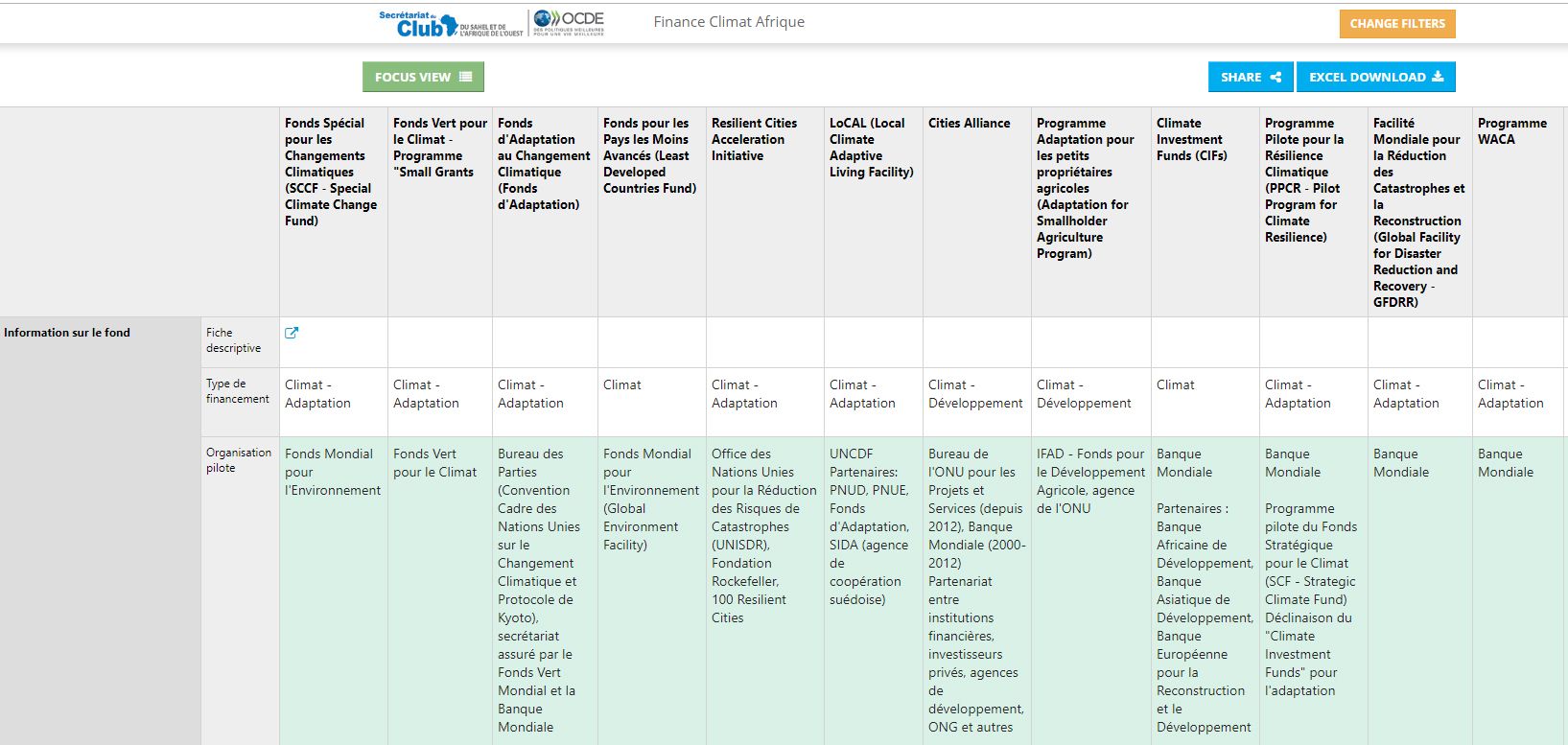

Climate financing

In order to seek funding for a climate change project, there needs to be a clear-cut problem that must be addressed: Would the project relate to planning, training, investment? What is the topic? With which partners?

It should be noted that reducing the risks of disaster is a separate topic that is particularly well funded.

The following activities are more likely to attract funding: research and dissemination of new information on the effects of climate change, analyses of vulnerabilities and planning strategies that integrate adaptation measures, and the setting up of small projects and training populations to mitigate risk of disaster. Many donors are also drawn to urban and cross-border aspects.

Co-financing is sometimes needed, especially with regard to seeking Green Climate Funding, whether for planning activities or investment. Development banks often provide co-financing for large amounts that States cannot cover.

Finally, many financing schemes for climate activities offer loans, so-called concessional or highly concessional loans (that is to say, at very low interest rates). In this case, the concerned State(s) must carry out the project because African local authorities, depending on the States’ governing laws, do not always have borrowing capacity. Increasingly stakeholder networks are calling on national agencies to be the intermediary that would provide technical engineering for sustainable development and climate action projects, but would also mobilise funds for local government.

Various West African States can create specific funds for the “environment” or even “adaptation”, but these funds are not always effective : Local stakeholders are therefore asked to present their projects to national authorities to seek their support and potential financing or pursue their support along with other partner institutions that have the technical engineering and/or financial means needed for the project.

The list set out below is a non-exhaustive, and above all, evolving inventory of financing mechanisms for cross-border local development projects related to the adaption to climate change.

Local authorities' access to funding for cross-border local development and climate resilience

There are programmes that provide financing, through subsidies, directly to local authorities, for example for climate planning. Direct financing provides local authorities with a greater sense of appropriation. However, for larger projects, state intervention is often requested for solvency reasons, provided that local authorities have the capacity to borrow directly. Nevertheless they do not always have this capacity. Firstly, a decentralisation framework should already be set up; and, secondly, national authorities should provide local authorities with flexibility in terms of activities and climate finance (which tends to be the case as the supervisory authority).

In addition, adaptation projects tend to support the national strategy developed within the framework of the National Adaptation Plan (under the 2010 Cancun Adaptation Framework), as adaptation must be a “country-driven” process, undertaken by the country concerned according to its needs.

In any case, within West African states’ current domestic legal systems, local authorities are not exempt from national authority’s supervisory power with regards to foreseen or effectuated loans. If the local authorities could raise funds directly, they would have greater ownership of projects, thus more room for manoeuvre in cross-border cooperation.

Local and regional authorities are at the forefront of climate change and have a better understanding of the specific issues within cross-border areas. Financial resources must be able to reach the local level for investments to benefit the most vulnerable local communities. Greater financial decentralisation (supported inter alia by United Cities and Local Governments, the Global Fund for Cities Development, C40, etc.) would increase the investment capacity of local and regional authorities for territorial development.

Donors should be encouraged to consider local and regional authorities as credible interlocutors and long-term partners and not just beneficiaries. In the short term, an agreement should be reached to establish financial intermediaries, namely financing institutions dedicated to communities where community groups sharing technical engineering services and projects are able to serve as a financial intermediary between international donors and local authorities for large-scale projects (for example, the Groupement Intercommunal des Collines in Benin).

The case studies

Dori (Burkina Faso) and Tera (Niger)

The following case study describes Dori and Tera, two non-contiguous settlements, about 95 kilometres apart, located on both sides of the Burkina Faso-Niger border. They form a network of cities considered as “twin cities”, separated by a few kilometres, functioning as a tandem due to flows, transit logics and interurban mobility.

Interview with Ahmed Aziz Diallo, Mayor of Dori (Burkina Faso)

Gaya (Niger)- Malanville (Benin)

This case study describes the Gaya-Malanville cross-border region. Developed along the Cotonou-Niamey route, the cities of Gaya (Niger) and Malanville (Benin) are 10 kilometres apart and separated by the Niger River. This cross-border agglomeration is the economic core of the Dendi region. In 2018, the border agglomeration of Gaya (Niger) and Malanville (Benin) had about 111 000 inhabitants of which 50 368 lived in Gaya and 60 806 lived in Malanville. It is estimated that in 2020, there will be a total of 135 000 habitants.

Lomé (Togo) - Cotonou (Benin) Coastal Corridor

This case study describes the Lomé-Cotonou cross-border axis, a corridor of coastal cities containing 1.7 million inhabitants. For ECOWAS, it is of strategic importance for regional integration. Along this axis, Lomé (the capital of Togo), forms a cross-border agglomeration with Aflao (Ghana), Aného (former capital of Togo) and Hillacondji (in the municipality of Grand Popo).

Partnership

This work has been be carried out in collaboration with the Transfrontier Operational Mission (MOT) and draws on its past experience collaborating with the African Union Border Programme, SWAC Members, including regional organisations, UCLG Africa and Climate Chance.

Interview with the Transfrontier Operational Mission (MOT)