The geography of violence in North and West Africa — a focus on borderlands

Violence in North and West Africa is far from homogenous geographically, with violent events increasingly occurring in borderlands.

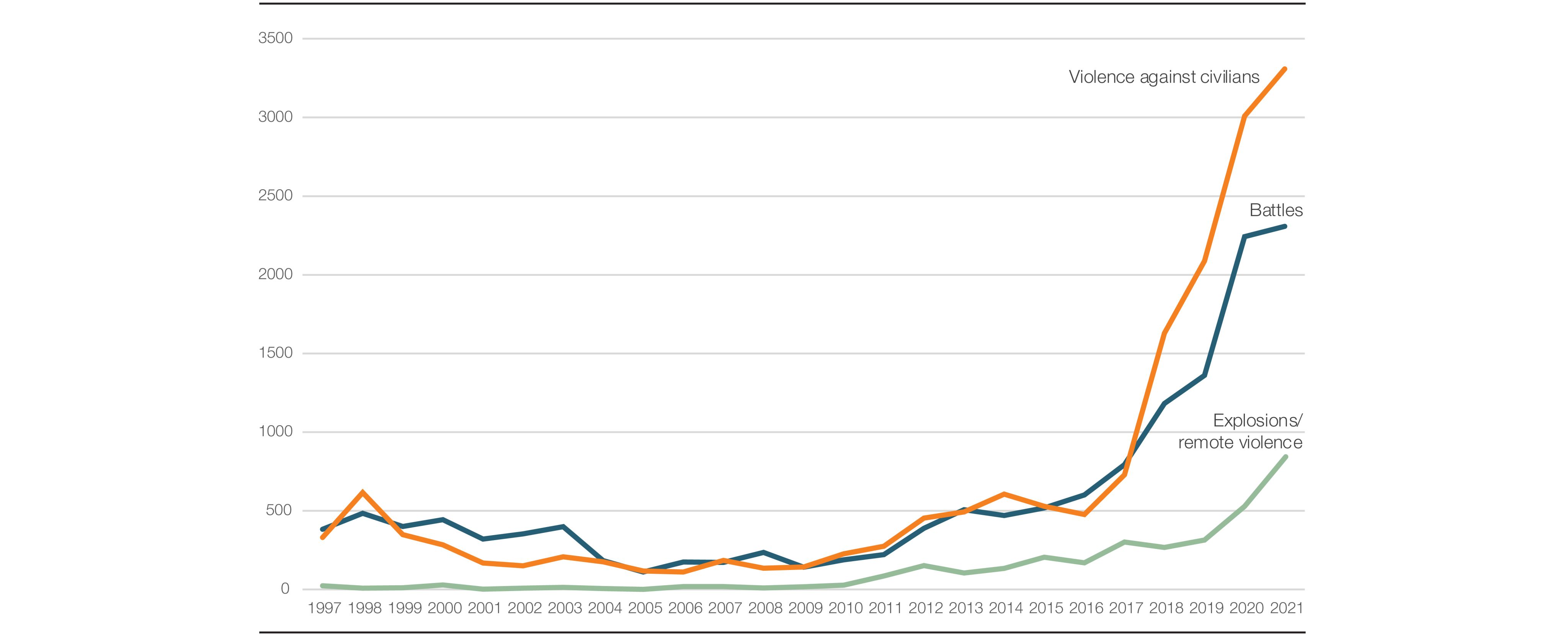

Violence has been increasing in North and West Africa since 2011. From 2015 to 2019, there were an average of 3 300 events per year and 12 600 fatalities.

In 2020 -2021, this number jumped to 6 800 events with 18 000 deaths per year.

Even more concerning, is that this increase is taking place despite considerable declines in violence in Libya and Algeria. The epicentre of violence has moved to Nigeria and the Mali-Burkina Faso-Niger border.

Violence against civilians has increased by 500% in West Africa since 2016

This is due in large part to the change in nature of conflicts as south of the Sahara, conflicts involve more and more actors such as secessionist rebels, religious extremists, self-defense groups and an increasing number of communal militias.

As the number of conflict actors has multiplied, violence has increased as have civilian casualties. With the increasing number of actors, responses have become more complex as conflicts have become more transnational, making greater regional cooperation necessary.

Number and types of events in West Africa, 1997-2021

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

One particularly disconcerting trend is borderland violence

In the first six months of 2021, 60% of victims of violent incidents were killed within 100 kilometres of a border.

Our latest annual report on Borders and Conflicts in North and West Africa, asks three questions about the connections between borders, borderlands and conflict:

Are borderlands more violent than other areas?

Is violence increasing in borderlands ?

Are some borderlands more violent than others?

To answer these questions we have used the Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator that was developed by the SWAC Secretariat/OECD. Security trends and patterns are analysed at multiple levels – local, national, regional and in border areas between January 1997 and June 2021, by analysing data from the Armed Conflicts and Events Database (ACLED) and qualitative analyses. This multi-scalar approach allows us to bring new insights to security challenges and suggest more place-based policies

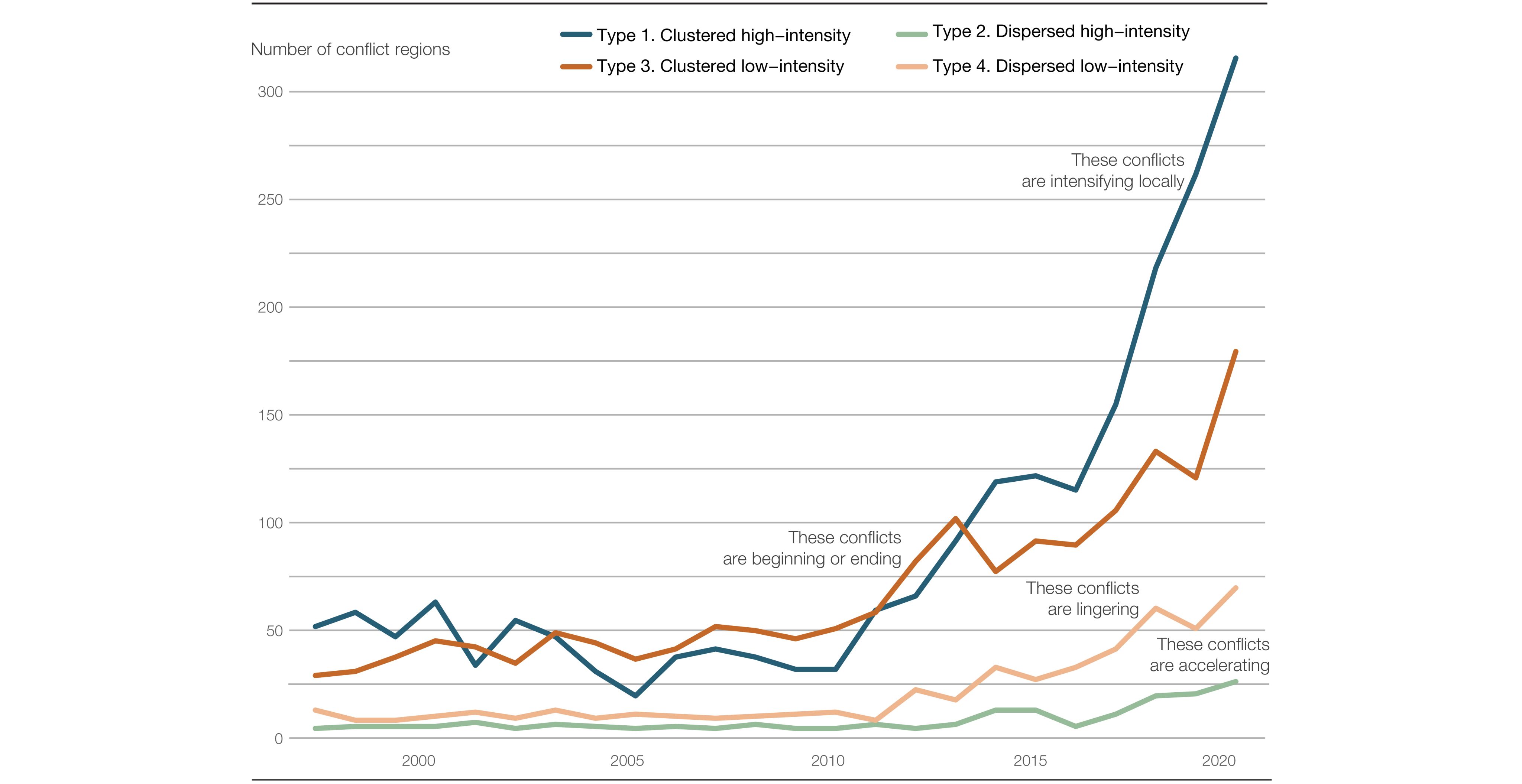

What can the Spatial Conflict indicator tell us about conflicts?

The Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator developed by SWAC Secretariat/OECD examines the changing geography of conflict in North and West Africa. The SCDi divides the region into 50 x 50 kilometre cells then classifies conflicts by looking at conflict intensity and conflict concentration. This classification makes it possible to understand where a particular area is in the conflict “life cycle”.

Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator, North and West Africa for 2021

The areas that are dark blue are of particular concern as they are hotbeds of clustered high-intensity violence in the middle of the conflict life cycle. Areas particularly concerned by clustered high-intensity violence are the Lake Chad region and the Mali-Burkina Faso-Niger border and Nigeria.

This violence is unlikely to diminish in the short term. As more and more areas move into this category each year, especially in borderlands; conflicts are intensifying where they already exist and are spreading where they did not exist before.

Number of conflicts by type, 1997-2021

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Are borderlands more violent than other areas?

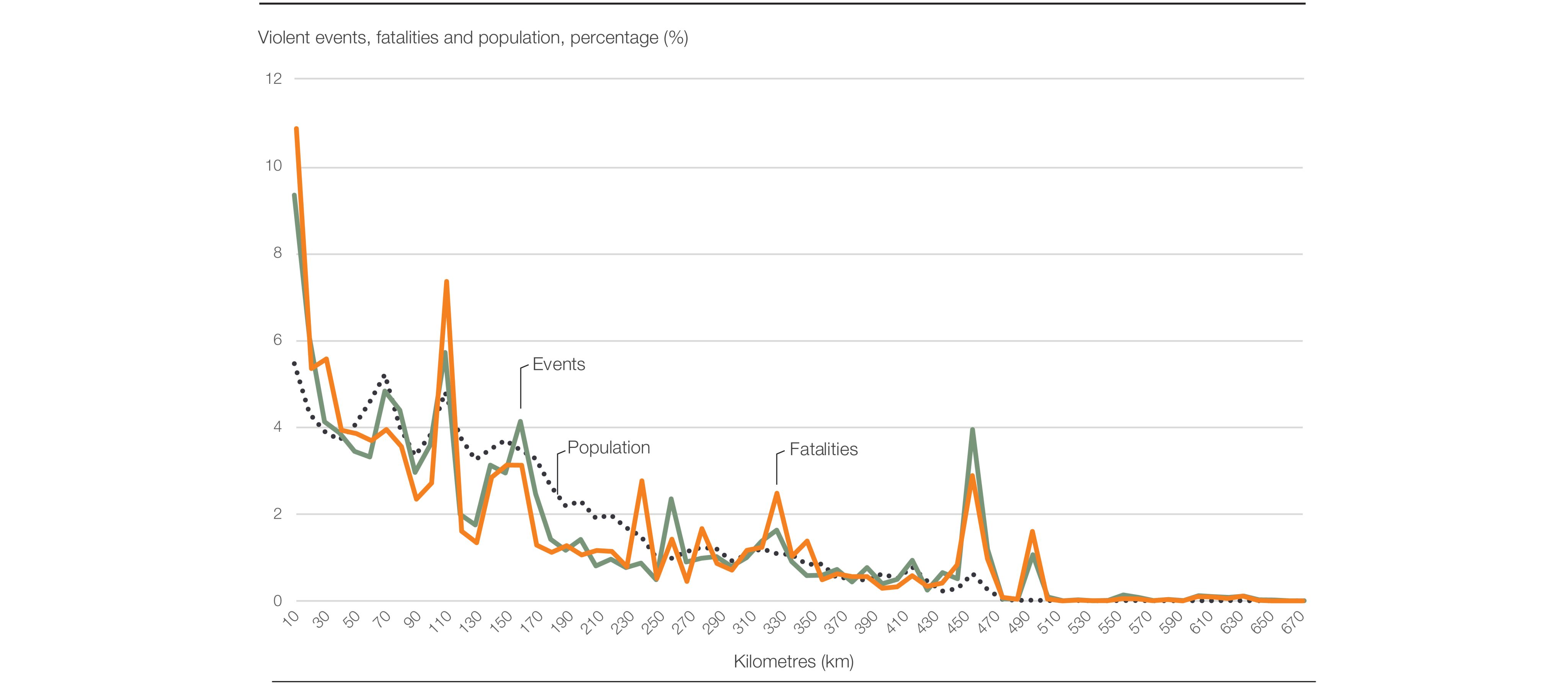

By analysing data from 21 countries across 23 years, it becomes clear that nearly 9% of all violent events occurred within 10 kilometres of a border, where 6% of the total population lives. At 20 kilometres from the border 15% of violent events occurred, and at 50 kilometres 25% of events occurred. This follows a classic distance decay-effect — the further from the border, the smaller the number of violent events observed. Therefore, we can say that borderlands are more violent than other areas.

Violent events, fatalities and population by border distance in North and West Africa, 1997-2021

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Is violence increasing in borderlands ?

Violence in borderlands is different from violence in non-borderlands. The epicentres of borderland violence are the Mali-Burkina Faso-Niger tri-border area and the Lake Chad region. Violence in borderlands has a larger share of high-intensity clustered violence than in non-borderlands. Where conflict is happening in borderlands, it happens intensely with a larger number of events occurring near each other. This type of violence is likely to endure.

Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator (SCDi) in border regions, 2020

Are some borderlands more violent than others?

By combining quantitative data on location of violent events with qualitative assessments in the form of case studies and an analysis of actor networks, it is possible to discern local, state and regional factors that have an impact on the level of violence in borderlands.

Violent actors exploit state weakness, notably in border areas. For example, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) has successfully exploited local tensions around access to land, herding rights and mobility to secure favour in the tri-border area. Since the creation of ISGS in 2015, nearly half of all violent events in the region have occurred within 50 kilometres of the Mali-Burkina Faso-Niger border.

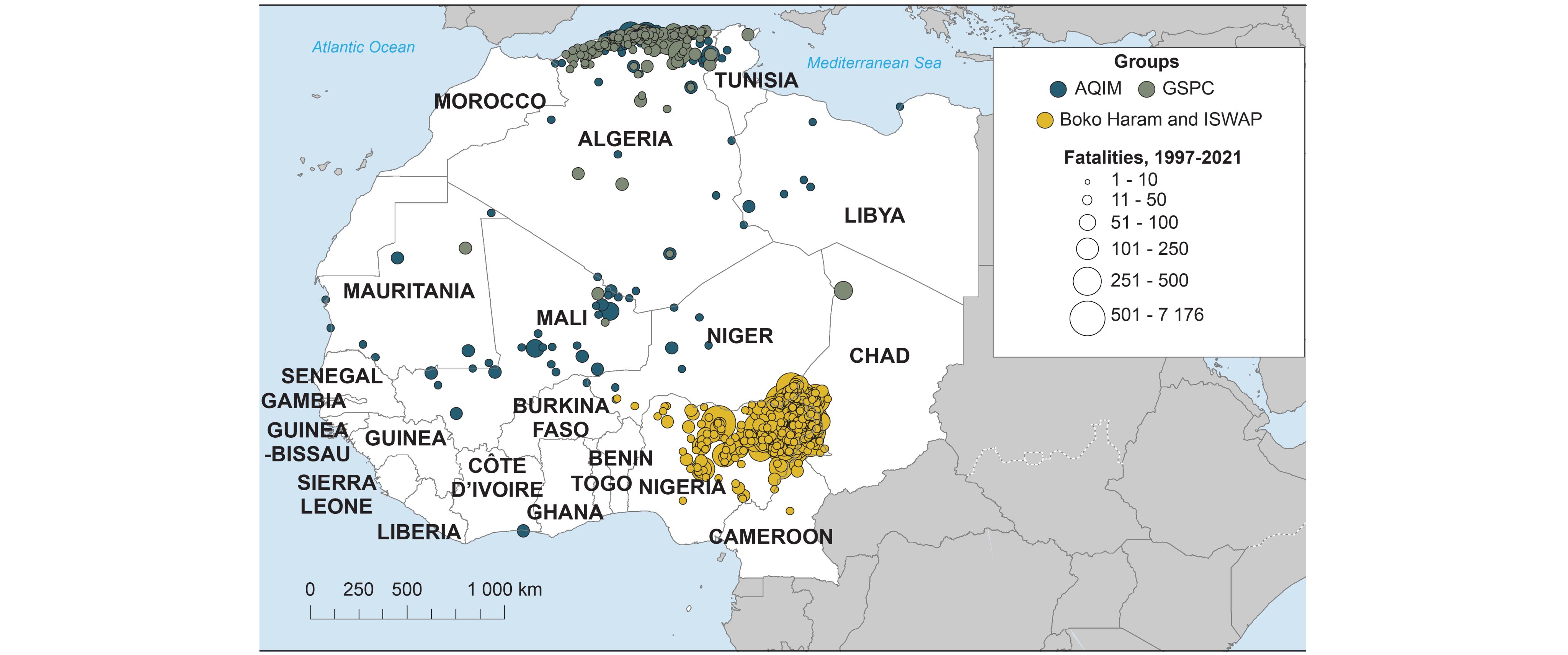

Violent events involving select transnational organisations, 1999-2021

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

As violent non-state actors are proliferating in the region, they are also becoming increasingly transnational and are driving the increase in conflict.

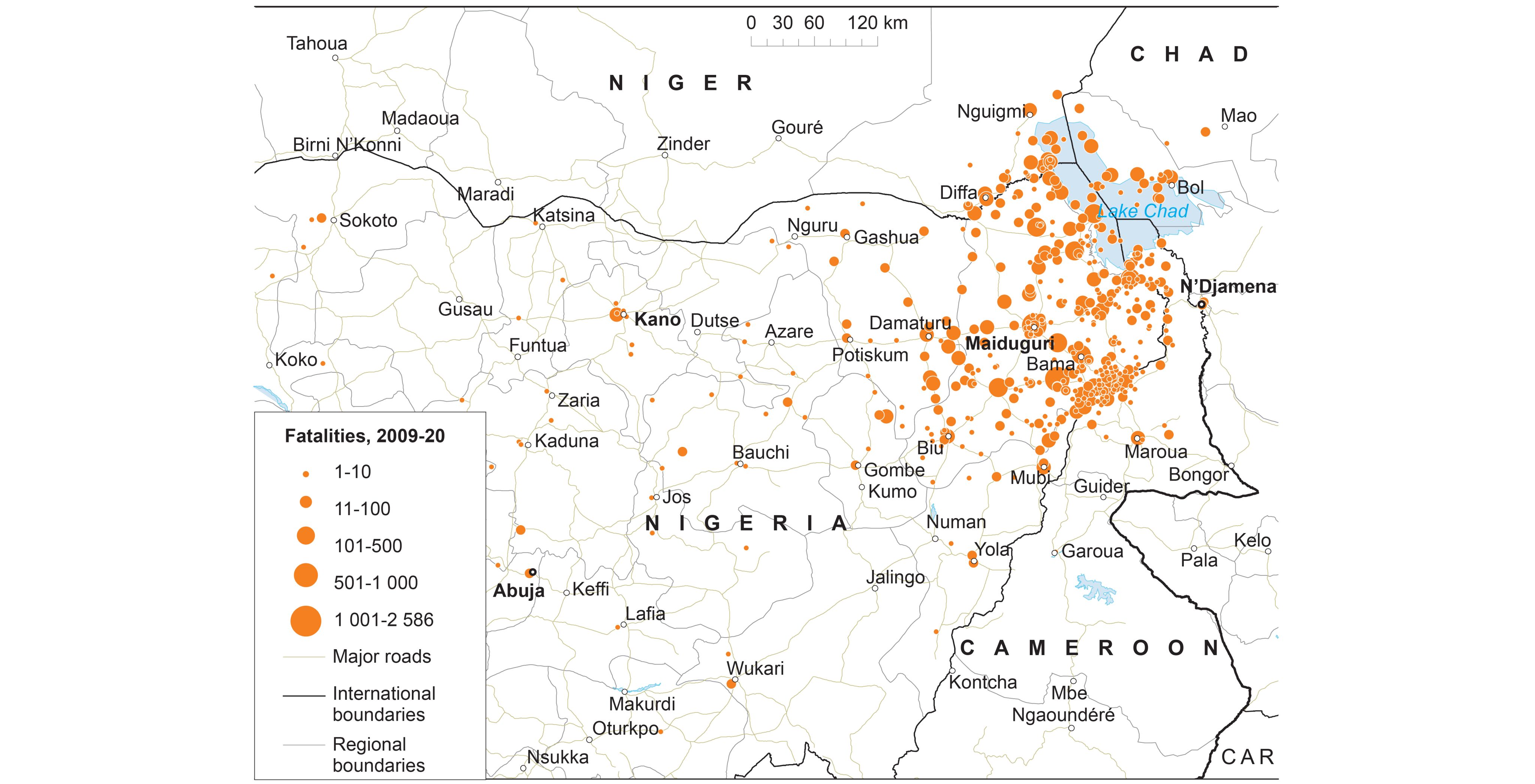

Where borders are porous and state authority is weak, violent groups often take advantage of the situation to develop safe havens, recruit new members and acquire supplies. Boko Haram for example responds to pressure applied by one country by moving activities to neighbouring countries. In 2013, when the Civilian Joint Task Force intervened to curtail Boko Haram’s activities in Maiduguri in Nigeria, this resulted in an escalation of attacks outside of the capital of this state and into parts of northern Cameroon.

Fatalities involving Boko Haram, ISWAP and government forces, 2009-20

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

Source: OECD-SWAC computations based on ACLED data. © 2022. Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat (SWAC/OECD)

How can we secure borders and reduce the levels of violence?

In order to attenuate borderland violence there are a number of policy options that can be implemented:

Border security and technologies should be reinforced

By continuing efforts on the part of multinational forces such as the Multi-National Joint Task Force, the G5 Sahel and greater investment in border monitoring resources and technologies. While regional bodies such as the Economic Community of West Africa (ECOWAS) and international development partners promote regional integration, they should also make border security a priority.

Build better infrastructure to promote national cohesion

Better integration of border regions and investment in infrastructure can help reduce the feelings of marginalisation in peripheral communities.

Invest in public services in border cities

Border cities play an important role in the regional circulation of goods and people, yet they often lack public services that would help them to become commercial hubs and centres of innovation. These deficiencies can be exploited by violent actors.

Protect civilians above all

As violence has increased in the region, so too have the consequences borne by civilian populations. The main concern of African states and allies should be the protection of the lives and livelihoods of civilians.